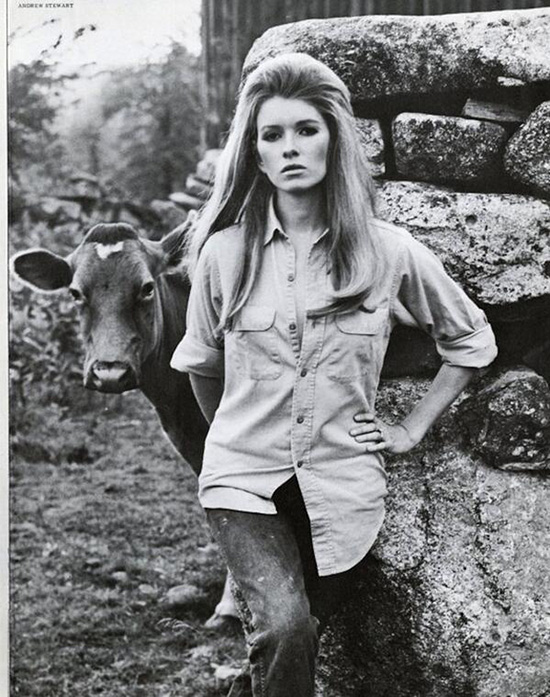

When I was in college dreaming of New York and a job in fashion, I followed the career of a young woman who seemed to burst onto the couture stage like a fleet-footed ibex. This was the 1980s of banking deregulation, Arnold Scaasi's red dresses for Nancy Reagan, Ivan Boesky, Malcolm Forbes' 70th birthday party in Morocco, Leona Helmsley, The Bonfire of the Vanities, and more cocaine than Jonah Hill ever imagined. The particular young woman I admired, Carolyne Roehm, came from Kirksville, Missouri, and in the fashion pages, her face looked midwestern fresh. She worked for years for Oscar de la Renta, and both were purported to have beautiful manners. Her designs were classically elegant with unexpected ladylike touches, executed in the most gorgeous fabrics. I see her influence in Tory Burch today.

I watched throughout the 80s as her star rose boldly and brightly. She launched her own fashion line to immediate accolades and shortly thereafter, married the man who put up the money for her collection. His name was Henry Kravis and he was known around town as the billionaire financier who sort of invented that 80s phenomenon, the leveraged buyout. But a nice guy.

Then one day as happens in all fairy tales, her star fell. Her husband's son was tragically killed in a car accident and shortly after, she shuttered her fashion house -- supposedly because Kravis pulled the plug. Next came divorce. And then an escape to Paris where she worked quietly in a flower shop. (Not just any flower shop -- she worked at Moulie Savart, probably the most famous little flower shop in all of Europe.) She eventually returned to the States, and began to repair herself at Weatherstone, her beloved estate in Connecticut, and the only property out of seven that she got in the divorce settlement. (The scuttlebutt at the time was that she didn't even own Weatherstone but instead was granted a life tenancy by her ex -- very Jane Austen.)

At Weatherstone, she threw herself into her garden. I think she transferred her affections to her flowers. Which is a very good and bad thing to do. Her flowers couldn't up and leave her, but they didn't bloom forever either. This impermanence of flowers fascinated Roehm and that is how she stumbled onto her next profession. She wrote a book about the gardens at Weatherstone and it sold like crazy. More books followed, and from the protective stone walls of Weatherstone, Ms. Roehm reclaimed her status as a woman of substance.

Then Weatherstone burned.

It devastated her. Aside from the obvious loss of the antique-filled home, she lost a significant collection of books, irreplaceable photos including those documenting her time working for Oscar de la Renta, and all the original sketches, fabrics and trimmings from her nearly twenty years as a designer. It was a loss of identity.

But she had those midwestern genes -- her father was a school principal and her mother a school teacher -- and she knew what she needed to do. She rebuilt Weatherstone and found the experience empowering. I read her blog and every spring, she complains about the lack of it in Connecticut. Which makes me feel for her. Her flowers are her amiable companions and when Mother Nature delays their arrival, she feels it.

Now that I'm finding my own way in a creative endeavor, I look at the life of this woman I have so admired and I see pain, suffering, sacrifice, and loneliness. Some bad decisions. And creative genius. She continues to intrigue me, and I have several collections in the shop which are inspired by her.

Carolyne Roehm's pink and green antique chinoiserie plates look stunning with roses and ivy in silver julep cups. She purchased these as a young woman with no expendable income, and they survived the fire. This photo is from her book, At Home with Carolyne Roehm.

This is Ms. Roehm's greenhouse. The butterfly and bug specimens were purchased from Christopher Marley, an artist who creates stunning mosaics of insects. Read about how he turned a fear of bugs into his life's work on DesignMilk or peek at his incomparable art in his gallery, Pheromone.*

I loved putting together this butterfly and beetle collage, inspired by the room above. The platter is Spode and it's such a blowsy pattern. For more information about this collection, please click here or on the photo. Photo by Renn Kuhnen.

Ms. Roehm's "Bird Room". It is a breathtaking space in cool shades of blue with gold and white accents and of course, beautiful birds perched on brackets. She has used wall brackets for ages and they are coming back in style in a big way. More about this lovely room here.

My version of birds and brackets. I just listed this collection in the shop under the name Golden Songbirds on Dogwood Brackets. A cumbersome name. Either way, they somehow remind me of the Hans Christian Anderson fairytale. Photo by Renn Kuhnen.

I also admire Martha Stewart. Read why: